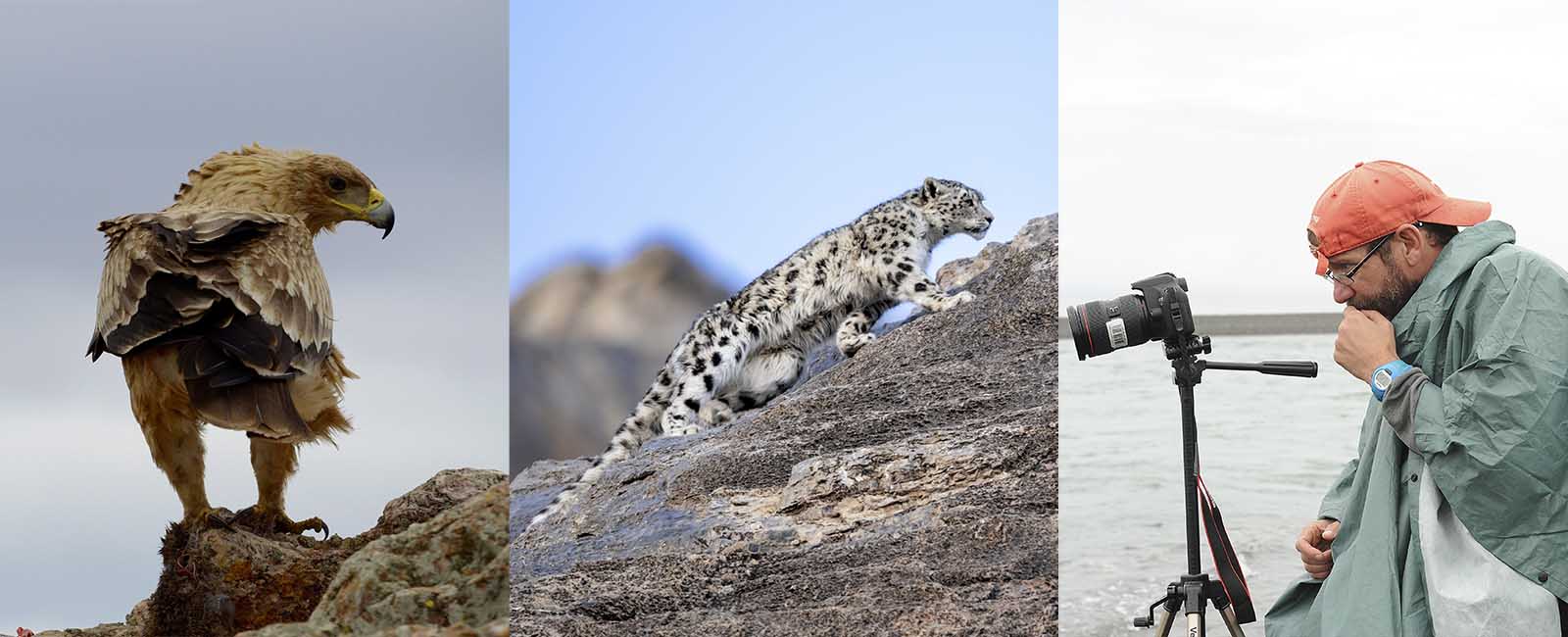

The BBVA Foundation recognizes the conservation of lynxes, eagles and vultures in Spain, the protection of snow leopards in Asia, and the environmental reporting of Clemente Álvarez

The conservation of the Spanish imperial eagle, the Iberian lynx and the cinereous vulture in Mediterranean forest and woodland; the protection of the snow leopard and the rugged mountain systems of Asia where this endangered feline makes its home; and the rigor and innovation that characterizes the environmental reporting of Clemente Álvarez, head of El País’s Climate and Environment section, take the honors in this 17th edition of the BBVA Foundation’s Biodiversity Conservation Awards.

21 September, 2022

Fundación CBD-Hábitat wins the award in the Biodiversity Conservation Projects in Spain category “for its pioneering work on behalf of the conservation of Mediterranean forest and woodland and some of its most emblematic species, like the Spanish imperial eagle, the Iberian lynx and the cinereous vulture,” in the words of the prize jury. For more than twenty years, the citation continues, the awardee organization “has successfully integrated a solid scientific base with effective on-the-ground work producing proven results.”

The BBVA Foundation Worldwide Award for Biodiversity Conservation has been bestowed on the International Snow Leopard Trust “for its excellent work on conserving the last remaining populations of the snow leopard, one of the planet’s most endangered species.” By building an alliance between the governments of the twelve countries in the feline’s range, the trust, says the jury, “has obtained its first results in a species which stands as a symbol for the conservation of the natural and cultural heritage of Asia’s mountain regions, home to the world’s highest peaks.”

The award for Knowledge Dissemination and Communication in Biodiversity Conservation in Spain has gone to journalist Clemente Álvarez, head of the Climate and Environment section of daily newspaper El País, “for his exceptional contribution to environmental reporting based on rigor, journalistic innovation and the creation of new spaces and narrative formats,” remarked the jury deciding the award, describing the new honoree as “an outstanding exponent of the best environmental journalism being produced in Spain,” with a style that “eschews classical formats in favor of a more practical, everyday approach, without ceasing to engage in the big debates around climate change and biodiversity conservation.”

A mosaic of “biodiversity guardians”

Conserving global biodiversity stands as one of the defining challenges of our time, alongside climate change. The latest reports from leading scientific organizations like IPBES and the IUCN warn that a million animal and plant species are at risk of disappearing, and that extinction is advancing at up to 1,000 times its natural rate. The first line of defense against this runaway environmental crisis, documented through scientific study, is occupied by the “guardians of biodiversity” distinguished by these BBVA Foundation awards: people and organizations that have achieved solid, lasting progress in protecting nature, and the media professionals who disseminate the best scientific knowledge and information on the environmental crisis in order to educate and raise society’s awareness of the scale of the challenge.

Over their seventeen editions, the Biodiversity Conservation Awards have found their way to a diverse set of organizations that have taken effective steps to protect nature, from major ecologist and naturalist organizations like WWF and SEO/Birdlife to local associations concerned with a single species like the bearded vulture or Cantabrian brown bear or specializing in the preservation of ecosystems like wetlands or the Mar Menor, as well as public agencies undertaking vital tasks for the protection of nature, among them environmental police force SEPRONA or the Environmental Prosecutor’s Office. At the same time, the Dissemination and Communication category has reflected the many and varied ways of amplifying the conservation message, with awards for media journalists and other communicators disseminating knowledge of the natural world through multiple channels and formats, from illustration and photography to audio recordings and the making of film documentaries.

Together, the BBVA Foundation’s biodiversity awardees form a mosaic that reflects how the global biodiversity crisis is a complex, many-faceted problem that demands an array of strategies acting on different levels and a firm, long-term commitment if we are to make any significant headway.

The awards for projects in Spain and worldwide each come with a cash prize of 250,000 euros, while the communication award is funded with 80,000 euros, giving a combined monetary amount that is among the largest of any international prize program. The jury deciding the awards is made up of scientists working in the environment field, communicators, experts in areas like environmental law and policymaking, and representatives of conservationist NGOs who bring to the table complementary viewpoints on nature conservation.

Biodiversity Conservation Projects in Spain: CBD-Hábitat

Over two decades of conservation work at the service of the lynx, the imperial eagle and the cinereous vulture

In the mid-1990s, the Iberian lynx was on the verge of extinction, its population down to fewer than 100 individuals. And another two of the Iberian Peninsula’s emblematic species, the Spanish imperial eagle and the cinereous vulture, were struggling with food shortages due to declining rabbit populations and the ban on leaving animal carcasses out in the open following the outbreak of mad cow disease.

It was against this grim backdrop that Fundación para la Conservación de la Biodiversidad y su Hábitat (CBD-Hábitat) came into being in 1998 with the aim of saving these species and restoring their natural habitats. “The Foundation has a multidisciplinary team made up of biologists, civil engineers and other experts with a combination of research and conservation experience,” explains the organization’s director, Nuria El Khadir Palomo.

One of its main lines of action is focused on the conservation of these Mediterranean woodland species in alliance with the rural world. The organization has made it its job to perform a mediating role between private landowners and the administration, and has become a pioneer in land stewardship in Spain, acting as an advisor for the sustainable management of private estates, while demonstrating the benefits of maintaining a well conserved habitat. “In 1999 ourselves and WWF were the first in Spain to apply the stewardship agreement model, given our interest in species found largely on private lands. So we went from door to door talking to estate managers and owners, explaining that we wanted to conserve these species. At the same time, we were raising funds, designing strategies and getting them implemented on the ground,” El Khadir remarks. This methodology has since become a standard practice among many Spanish organizations.

“We started out in Sierra Morena, working with 10 estates as a kind of test case. Our experience was that we learned a lot from exchanging information and advice, since they were already taking their own steps to conserve the remaining lynxes roaming their estates,” she adds. “Trust is vital; without it, stewardship agreements cannot function.”

What sets this organization apart from other lynx conservation actors is the fact that they deal directly in situ with landowners, livestock breeders, farmers and hunters. “We like to define ourselves as nature’s allies on the land. Our work has shown that actors as diverse as public authorities, conservationist organizations, firms, landowners, farmers, livestock breeders and hunters can work together and that this mix of profiles operates to the benefit of conservation.”

In the lynx’s case, there are currently 548 individuals under surveillance in historic ranges on the Sierra de Andújar and a further seven reintroduction or expansion areas in Jaén, Extremadura, Ciudad Real and Montes de Toledo. The foundation has participated in the reintroduction of over 160 lynxes in these areas, contributing to a population growth that has seen numbers rise from 100 to over 1,100 in the space of 21 years. In the case of imperial eagles and cinereous vultures, initiatives like the radio tagging of 88 raptors, the rescue and recovery of 28 individuals, the inventorying of threats such as dangerous power lines, or the installation of stationary and mobile feeding middens have achieved a 30% population increase on estates where stewardship agreements are in place.

The resources deployed for their conservation have indirectly aided other Mediterranean woodland animals, giving them the status of an “umbrella” species. Among the main beneficiaries is the European rabbit, for which more than 6,250 shelters have been built, with an occupancy rate of over 75%, along with 484 water points and 270 feeding troughs. Also rabbit hunting rights have been leased for a period of six years in areas of the Sierra de Andújar where breeding lynx females are found.

“We have designed a tube system for rabbits, which is like a burrow they can shelter in, safe from predators. And we have gone on improving it over time.” Another of the foundation’s innovations is a supplementary feeding system for the lynx, especially so females with cubs can feed naturally when not enough rabbits are available.

The next step is to ensure that conservation finds its place in government funding priorities. “The projects we work on need a lot of funding because they are long term. That’s why a prize like this is so important for small organizations like ours. It brings us not only recognition but a new income stream to pursue our objectives at a time of uncertainty. A lot of funds are being channeled to the likes of renewable energies or climate change, which are obviously important, but the fact is that nuts and bolts conservation work, which is what we do, is being left out. We occasionally look for suitable options among public funding calls, but feel this could distract us from our purpose, which is the increasingly urgent need to conserve species and habitats.”

Worldwide Conservation Award: International Snow Leopard Trust

An alliance of 12 Asian countries to save the snow leopard

The snow leopard is a predator at the apex of the food chain in its habitat, making its conservation essential for the health of the whole mountain ecosystem of the Himalayas and other great Asian ranges. This region, known as the Earth’s “third pole,” is home to 14 of the world’s highest peaks and almost 100,000 square km of glaciers.

“It’s an astonishing animal, the product of millions of years of evolution that have allowed it to adapt to the harshest conditions of extreme cold, and an ability to hunt its prey on the steepest high-mountain slopes,” says Charudutt Mishra, Executive Director of the International Snow Leopard Trust, in an interview shortly after learning of the bestowal of Worldwide Conservation Award for its work on protecting this endangered cat. “The species is amazing in itself, but furthermore when you protect it, you are also helping to protect a whole ecosystem and its associated biodiversity.”

The snow leopard’s range sums two million square kilometers and extends across the territory of 12 Asian countries (Afghanistan, Bhutan, China, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Nepal, Pakistan, Russia, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan). This is an ecosystem that provides absolutely vital services, starting from the supply of water to a third of the world’s human population, who depend for drinking water and irrigation on the rivers that flow down from these mountains.

The species currently faces multiple threats. Firstly, it suffers “revenge killings,” Mishra explains, by farmers whose herds are attacked by the feline, as well as poaching and illegal wildlife trafficking. Further, over the past decades its habitat has become increasingly fragmented due to major infrastructure development, primarily highways, mines and dams. And to all these risks must be added climate change, which has heightened the dangers confronting the species and the whole mountain ecosystem of Asia, due to the frequency and intensity of extreme climate events and natural disasters “The entire region,” Mishra observes, “is warming nearly two times faster than the Northern Hemisphere average.”

It was this fragile situation that led to the creation of the International Snow Leopard Trust over forty years ago, in 1981. In the last decade, the organization helped create an “intergovernmental alliance,” which has brought together different organizations and promoted cooperation between the governments of the 12 countries where the snow leopard lives in order to protect the species and its ecosystem. In 2013 officials, politicians and conservationists arrived at a common conservation strategy enshrined in the Bishkek Declaration, signed by the governments of the 12 range countries, to cooperate in the conservation of the cat and its habitat, and formed the Global Snow Leopard and Ecosystem Protection Program.

“This pledge testifies to the power of nature conservation to foster international cooperation, even among countries engaged in disputes,” says Mishra. “With the snow leopard’s habitat taking in so many territories, its conservation would not be possible without cross-border cooperation.”

The project has identified 24 protection areas (some 500,000 km sq.) covering 25% of the species’ range. Of this, conservation measures are already being rolled out in about 140,000 km sq. with the support of each country’s authorities, the scientific community, NGOs, companies and local communities. Mishra highlights in particular the effectiveness of the anti-poaching patrols formed by over 400 forest rangers trained under this effort, the installation of fencing to protect livestock from snow leopard attacks and, thus preventing conflicts with local communities, the development of sustainable livelihood and nature tourism projects, and the launch of environmental education programs to raise public awareness of the value of conserving the species.

According to some estimates, as few as 4,000 individuals of snow leopard survive. Mishra insists however that this is “a preliminary approximation,” adding that the Global Snow Leopard and Ecosystem Protection Program is facilitating the first scientifically robust, large-scale study to determine the size and range of the current population, with results due within a year.

“We have to understand,” he explains, “that conserving nature is never just a local matter. It is a global challenge that concerns us all, governments, firms and civil society. As the pandemic has shown, we live in an interconnected world, so what is happening with biodiversity in a remote mountainous region of Asia can impact directly on the other side of the planet.”

Knowledge Dissemination and Communication: Clemente Álvarez

24 years putting environmental news at the heart of the public agenda

Clemente Álvarez (Madrid, 1973) has been working to push environmental news up the public agenda since 1999, when he signed a front-page article in La Razón newspaper detailing the refusal of the then U.S. President, George W. Bush, to back the Kyoto Protocol against climate change. “The crucial thing in achieving the widest possible readership is to really want it. Often when you don’t succeed it’s because you’re not really trying. With so many stories currently competing for the public’s attention, you have to stop them looking elsewhere and get them to focus on the environmental issues that will shape our planet’s future,” said Álvarez shortly after hearing of the award.

In his more than twenty years as an environmental journalist, Clemente Álvarez has been involved in the launch of dedicated sections in La Razón, Soitu, elDiario.es and El País. In 2014 he founded the specialist magazine Ballena Blanca then went on to create the environment section of Univision, one of the top Spanish-language channels in the United States, working there as chief editor for two years.

He has been hailed by the jury for “his exceptional contribution to rigorous environmental reporting” and as “an outstanding exponent of the best environmental journalism being produced in Spain.”

The UN’s 2009 Climate Summit in Copenhagen gave him a fresh opportunity to get environmental news into the headlines: “It is true that for reasons of urgency climate change at times overshadows the biodiversity crisis. But it’s important to remember that the two issues are closely intertwined, to the extent that some anti-climate change measures, if not implemented with care, can actually threaten biodiversity. I am thinking, for instance, of the current drive to increase take-up of renewable energies. Reporting on both issues should therefore go hand in hand,” he explains. The headline in this case appeared in El País, the newspaper he has been writing for since 2004 and whose Climate and Environment section, which he founded and has lead since 2020, reaches around one million readers every month: “I’ve been lucky in that all the media where I’ve worked have shown a commitment to environmental reporting. This is certainly true of El País, where they believe in the Environment and Climate agenda and have happily given it space and resources.”

“Journalistic innovation and the creation of new narrative spaces and formats” are among his other qualities singled out by the jury, presumably in recognition of his pioneering presence on social media: “I reported on the 2009 climate summit via Twitter, in 140 characters. Most journalists were clustered around the teletype machines or running down the corridors trying to keep up with everything going on, while I had my networks running and could not only follow the various events unfolding at the same time, but had videos of the demonstrations taking place on one site, the protests at another … that was something really new. Journalistic rigor is always a constant, as is double checking news, but when you suddenly get these tools to reach many more people and do different things, I think our duty is to try them and use them.”

Clemente Álvarez approaches environmental reporting from multiple angles: from the extinction risk facing a local species to the great global problems of deforestation, desertification or thawing ice caps. He also believes we need to appeal to and engage with the widest possible number of actors: “This is not a minority issue interesting only a few: it concerns everyone, even if they prefer to ignore it. A fundamental part of environmental reporting is to make the issues feel relevant to people. There has always been this tendency to focus on distant forests and exotic places, but the journalist has the vital job of bringing the big issues closer to readers’ lives. To explain that the impacts experienced far away are part of a global process that will affect them too.”

In any case, he adds, “any environmental news item must have its base in science, in validated knowledge, regardless of the format, subject matter, channel or medium. You have to make experiences feel real and connect with the personal aspect, but always with scientific rigor.”

Besides appearing in purely journalistic formats, Clemente Álvarez has made his mark in other domains, scripting the comic Cuaderno de campo de una vida en Doñana (2019) about the life of Miguel Delibes de Castro, and creating work for the theater and group exhibitions.

Jury members

The jury in this edition was chaired by Rafael Pardo, Director of the BBVA Foundation. Remaining members were Araceli Acosta, a journalist specializing in environmental issues, Alberto Aguirre de Cárcer, editor of daily newspaper La Verdad de Murcia, Laia Alegret, Professor of Paleontology and IUCA researcher in the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Zaragoza, Juan Carlos del Olmo, General Secretary of WWF España, José Luis Gallego, head of the environment section of El Confidencial, Esteban Manrique Reol, Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens (CSIC), Isabel Miranda, editor of the Environment in Society section of newspaper ABC, Carlos Montes del Olmo, Professor of Ecology and head of the Socio-Ecological Systems Laboratory at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Antonio Vercher, Chief Public Prosecutor for Environment and Land Planning in the Spanish Ministry of Justice, and Rafael Zardoya, Director of the Spanish Museum of Natural Sciences (CSIC), with Laura Poderoso, Deputy Director of the BBVA Foundation, acted as technical secretary.